The Walt Disney Co. has said it is suing a Hong Kong jewellery company due to the illegal sale of Mickey Mouse ornaments.

The international media and entertainment conglomerate filed a lawsuit in federal court in Los Angeles on Wednesday against the Red Earth Group, which sells jewellery online under the name Satéur.

Disney says the marketing and branding of the rings, necklaces and earrings in Satéur’s “Mickey 1928 Collection” violate its trademark rights and that the Hong Kong company is deliberately trying to fool customers into thinking the pieces are official Disney merchandise.

Disney’s lawsuit claims that Red Earth is “intentionally trying to confuse consumers” with the “Mickey 1928 Collection” and the impression created “suggests, at a minimum, a partnership or collaboration with Disney.”

Satéur, the suit alleges, “intends to present Mickey Mouse as its own brand identifier for its jewelry merchandise and “seeks to trade on the recognizability of the Mickey Mouse trademarks and consumers’ affinity for Disney and its iconic ambassador Mickey Mouse.”

The lawsuit seeks an injunction against Red Earth trading on Disney’s trademark in any other way, along with monetary damages to be determined later.

The lawsuit is indicative of Disney’s continued efforts to protect its intellectual property from unauthorized appropriation.

Although the earliest version of Mickey Mouse entered the public domain last year, the company still holds trademark rights to the character.

Even if a character is in the public domain, it cannot be used on merchandise in a way that suggests it is from the company with the trademark, as Disney alleges Red Earth is doing.

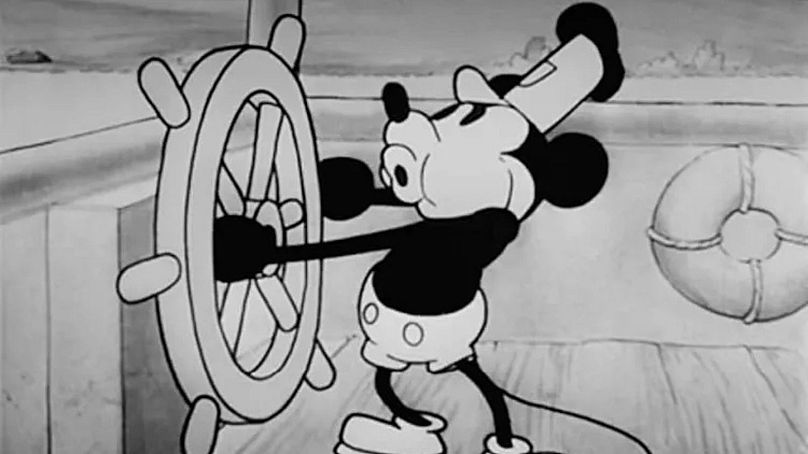

Mickey Mouse first appeared publicly in the short film Steamboat Willie in 1928. That version of the most iconic character in American pop culture is now free from Disney’s copyright and creators are able to make use of only the more rat-like, non-speaking boat captain from Steamboat Willie.

“This is it. This is Mickey Mouse. This is exciting because it’s kind of symbolic,” said Jennifer Jenkins, a professor of law and director of Duke’s Center for the Study of Public Domain, last year.

“It’s sometimes derisively referred to as the Mickey Mouse Protection Act,” Jenkins added. “That’s oversimplified because it wasn’t just Disney that was pushing for term extension. It was a whole group of copyright holders whose works were set to go into the public domain soon, who benefited greatly from the 20 years of extra protection.”

The widely publicized moment Mickey Mouse entered the public domain was considered a landmark in iconography going public.

Other famous animal characters like A.A. Milne’s Winnie the Pooh and Tigger recently joined the public domain. This resulted in several horror films like the gouge-your-eyes-out-terrible Winnie The Pooh: Blood and Honey.

Predictably, Mickey Mouse was also turned into a cheaply made slasher, Mickey Mouse’s Trap. It was released last August, and it turned out to be just as dreadful as the bloodthirsty ursine’s movie.

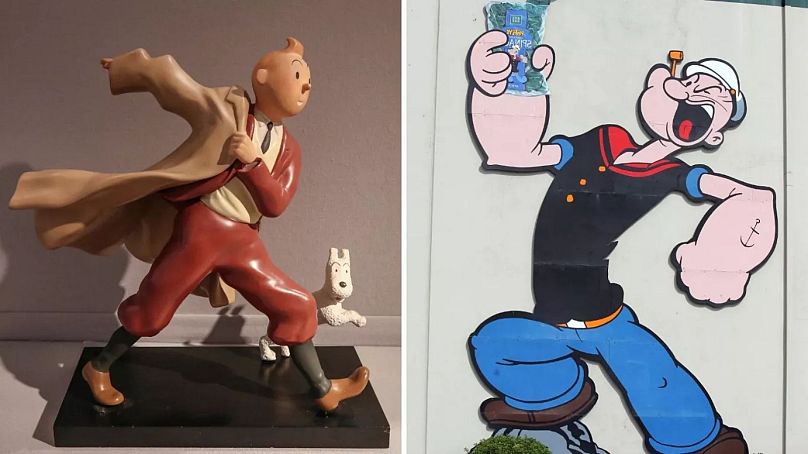

As of this year, two other pop culture figures entered the public domain: Popeye the Sailor can punch without permission and intrepid kid reporter Tintin can investigate freely.

The two classic comic characters who first appeared in 1929 are among the intellectual properties in the public domain in the US as of 1 January 2025 – meaning they too can be used and repurposed without permission or payment to copyright holders.

Certain noteworthy books also became public, including William Faulkner’s “The Sound and the Fury,” Ernest Hemingway’s “A Farewell to Arms” and John Steinbeck’s first novel, “A Cup of Gold,” from 1929.

There’s also British novelist Virginia Woolf’s “A Room of One’s Own,” an extended essay that became a landmark text in feminism from the modernist literary luminary.

Elsewhere, early works by major figures from the early sound era of moviemaking made their debut in the public domain in 2025, including Alfred Hitchcock’s Blackmail – a film shown at last year’s Festival Lumière in Lyon, France.